"Mother Nature was giving us a clear message about the health of the river system, but it was not heeded," admitted local mayor Kym Hughes. [“Mayor: How we failed to heed the vital warning signs,” http://blogs.news.com.au/adelaidenow/guestblogger/index.php/adelaidenow/comments/kym_chugh/] McHugh organized a march of mourning across that Bridge on August 10th. About 5,000 people stopped in the middle for two minutes' silence to “underscore this 11th hour bid to save the nation's greatest river,” said McHugh. ["Crowds gather for rally at Murray River." http://www.thedaily.com.au/news/2008/aug/10/aap-crowds-gather-for-rally-at-murray-river] McHugh's confession must be a bitter pill for the Ngarrindjeri to swallow, for all along they have been making strong statements about the need to protect Ruwi. Ngarrindjeri women's sacred law/lore warned what would happen if the Hindmarsh Island Bridge cast its concrete shadow over Living Waters.

Perhaps the reason Mother Nature and the Ngarrindjeri grandmothers weren't listened to was because decision-makers have been stuck in a medieval mindset: dominion over rather than cooperation with Mother Nature.

The word “weir,” for example, has a warrior ethos. It was derived from the Old English werian, to defend and protect, says John Ayto. [Dictionary of Word Origins, p570] In Britain the first “serious” damming (damning?) of rivers was undertaken by medieval millers. The feudal laws of Norman invaders placed the mill-dam under the tight control of the manorial landowner. The term for such a dam is “impoundment” which has the clear meaning of taking water into formal custody. Medieval laws, such as thirlage, which reaped great profits for the landowner seem to have coupled inextricably economic wealth and water-hoarding. Before the Normans' brutal land grab, riparian water-sharing rights which held that a stream of running water could not be possessed were a feature of a land held in common. The Norman Conquest legitimized water-hoarding and entrenched water injustice in its society to the gain of a privileged few. Seems a habit hard to break.

Behaving badly over water began in Australia with colonization. It is a history of hoarding. The gap between water supply and water demand is as old as the province of South Australia. My red-haired Scottish forebear was a water-carter in 1840. (It's been like deja vu watching the water-trucks at Narrung this year.

"Disputes between the three colonies about the river started as soon as Victoria was declared separate from NSW in 1850," point out Daniel Connell. ["Federation? Managing the Water in the Murray-Darling Basin-a historic perspective." http://www.gardenhistorysociety.org.au/pdfs/Daniel%20Connell%20Paper%20AGHS%20Conf%20Oct%2007.pdf.]

In South Australia, the Rankines, a family of Scottish migrants, probably weren't the first to behave badly over water. But according to Jim Marsh, Barrage Superintendent at Goolwa. they wanted to “try and stop the ingress of sea water into that reach, to hold a pocket of fresh water for their stock for the summer.” So they were probably the first to build a Murray weir: a wooden weir across Mundoo Channel. Marsh didn't say when. Probably around the 1850s. No thought for the First Peoples, the Ngarrindjeri, for whom this area is particularly sacred. Stumps of the weir apparently still remain near the Mundoo Barrage. One of Marsh's stories blames dynamite for its demise. [Rose Geisler, Alexandrina Local History Archive. http://www.stateheritageareas.sa.gov.au/pdfs/stories_goolwa_marshjm.pdf.] Now, the Ngarrindjeri who traditionally used fire technology for environmental renewal, have yarns that hint at pyrotechnics to rid Ruwi of harmful structures.

In 1863, lobbying began to lock up the River Murray . When the river was a major highway, paddlesteamers road-trains, the "inland desert" a prize for land-grabbers, seasonal low flows impeded “progress.” More bad manners: NSW, Victoria and South Australia disputed ownership and failed to reach an agreement, . [“Lock and Weir No 1,” http://www.aussieheritage.com.au/listings/sa/Blanchetown/LockandWeirNo1/10733]

In 1880, upstream water “extractions” due to "desert" irrigation, together with drought, impacted severely on the lower lakes, write researchers Terry Sim and Kerri Muller. [“A Fresh History of the Lakes: Wellington to the Murray Mouth 1800s to 1935,” River Murray Catchment Water Management Board, 2004]

In the 1897/8 Australasian Federation Convention, more drought and depression meant management of the River Murray was debated with "fierceness." South Australia wanted its right to water enshrined in the national constitution. The other states wanted to protect their right to irrigate. Alfred Deakin suggested a formula for retaining state rights with the option for a federal authority. The latter was ignored, while one of the rare rights in the Australian Constitution. Section 100 states: “The Commonwealth shall not, by any law or regulation of trade or commerce, abridge the right of a State or of the residents therein to the reasonable use of the waters of rivers for conservation or irrigation.” [http://australianpolitics.com/constitution/text/100.shtml] In effect what the Australian Constitution enshrined was the right to squabble over water. The insistence of South Australia that the word "reasonable" be attached to "use of the waters" points to the fears it had about upstream behaviour. The legal battles continue to this day. ["High Court talks on Murray, Coorong." 15/08/2008. http://www.independentweekly.com.au/news/local/news/environment/high-court-talks-on-murray-coorong/1245685.aspx]

In 1902, upstream extractions lowered the lake to sea level, the water turned salty, water grasses rotted, reeking and contaminating both water and air, record Sim and Muller. Conditions were a “disaster,” said Mr F Garnet, Superintendent of the Point McLeay Mission, (Raukkan). He observed: “Despite the long drought, the waters of the lakes have always been sweet at this time of the year.” Wool-washing, the industry that supported the Ngarrindjeri community collapsed. Garnet lamented: “Its destruction means a loss of 200 pound per year to the natives.”

In 1902, a Federal Parliamentary Commission's enquiry into river levels recommended a proportional share of the river for the states in times of drought; the construction of storage works and weirs at the Murray mouth; and a complete system of locks. Vested interests used Section 100 of the Australian Constitution to thwart these measures.

In 1912, the SA Govt hired a Captain Johnson, Corps of Engineers, USA, to report on a scheme for “locking” the River Murray. The first lock was built at Blachetown in 1922.

In 1915, the River Murray Waters Agreement, designed to work with the Interstate Commission, a federal decision-making body, was signed between states. But the river agreement for management of the whole Murray-Darling Basin became a dud when a High Court challenge stripped the Commission of its powers, recounts Daniel Connell.

In 1935 a string of barrages began to be built near the Murray mouth to stop seawater flowing upstream for 250 kms. [“Effects of weirs, locks, barrages and dams,” http://www.slsa.sa.gov.au/murray/content/dwindlingRiver/wiersDamsIntro.htm] The barrages destroyed 90% of the estuarine environment. Power for the construction was provided by the paddle-steamer Capt Sturt. (My mum spent her school holidays on board. My granddad took snapshots. Deja vu again.) “Soon after the first locks were built,” the fishing forebears of Henry Jones observed that the freshwater crayfish began to decline. The species is now gone.

In 1967, drought stirred the SA govt to stop issuing Water Diversion Licences to irrigators. [Who Owns the Murray?ed Peter S. Davis & Phillip J Moore, pp 19, 48.] Professor of environmental law at Uni SA, Rob Fowler, has criticised licences as “a private property right” granted “over a public resource.” He asserted: “It was a market economy solution that just hasn’t worked.” [http://www.independentweekly.com.au/news/local/news/environment/high-court-talks-on-murray-coorong/1245685.aspx] Today, existing water licences are a complicated matter. The SA govt varies their conditions in order to control water allocation. Licences are divided into "a Water Access Entitlement, a Water Allocation, a Site Use Approval, a Water Resource Works Approval and a Delivery Capacity Entitlement." [http://www.dwlbc.sa.gov.au/licensing/swr/index.html] Each state has implemented different water allocating processes. In 1983, South Australia introduced water licence trading.

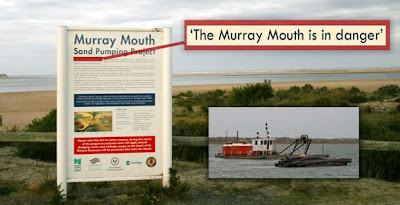

Due to reduced river flows, in 1981 the Murray mouth closed. The solution in 2002 was to dredge it open. It was supposed to be a $2m nine-month “Sand Pumping Project.” In 2005, Melissa Fyfe from The Age reported that dredging costs taxpayers $7m a year. [http://www.theage.com.au/news/National/More-help-to-keep-Murrays-mouth-open/2005/03/23/1111525218662.html.] Today dredging continues.

In 2008 the lower lakes reached record low levels. Here at Narrung, to prevent Lake Albert from collapse a $6m bund was built and pumping began at a cost of $600,000 a month. And recently, while the Federal govt announced a $50m pipeline for the Narrung Peninsula, the SA govt announced $30m for a weir at Wellington to secure Adelaide's drinking water.

Recent reports of upstream irrigators stealing water have emerged in the media. "Eight times the volume of Adelaide's drinking water" was being diverted from the Murray through unmetered pumps, claimed the SA Opposition Leader Martin Hamilton-Smith. ["Murray 'water theft' pumping angers SA Oppn." Aug 7, 2008. http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/08/07/2327092.htm?section=justin]. “60 cases of water theft “ are being investigated “in the Goulburn-Murray region of Victoria, Australia’s largest irrigation district, says researcher for the Water Integrity Network, Mark Worth. [“Crime and Drought in Australia’s Murray River Basin,” http://www.waterintegritynetwork.net/page/431]

Then, last week alleged illegal dams and irrigation channels on Qld's Paroo River, the healthiest tributary of the Murray-Darling, were condemned by SA's premier as “an act of terrorism against the nation.” [http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2008/08/15/2336850.htm?site=local] A moratorium on new dams and diversions had been put in place in 2001 by the Qld and NSW governments.

This week rural writer Asa Wahlquist reported that over the past years Queensland irrigators have been taking "record amounts of water from the Murray-Darling Basin," while "other state governments wound back irrigator allocations." ["Murray River drained by Queensland," August 21, 2008, http://www.theaustralian.news.com.au/story/0,25197,24215665-5013871,00.html] "This sort of behaviour, it is putting entire regions along the Murray-Darling Basin on their knees," said spokesperson for South Australian Murray Irrigators, Tim Whetstone. "At the moment, for the people who are up the top of the basin, it is first-in, best-dressed, showing no concern for anyone down lower. It is un-Australian."

Meanwhile, the river is losing its vital signs. The Murray Darling Commission states that public storages are holding 4,800 gigalitres of water: 21% of capacity. But the amount of water available to flow down the river can't be determined accurately, because of water diverted into the ownership of states and private landholders. This needs to be rectified urgently.

Cha bhi fios aire math an tobair gus an tràigh e. The value of the well is not known until it goes dry.

1 comment:

Post a Comment